While self-publishing a book has always been an option, a lot of authors still opt to wait – to see if they can get a publisher to give them a nod of approval.

Because for years traditional publishers were the center of the universe.

But the recent DOJ – Penguin Random House antitrust trial has brought a lot of that into question. As have some recent changes at Barnes & Noble.

So I want to dedicate a blog post to this news, without getting too far into the weeds with the trial, and look at some of the high-level takeaways of the future of working with a publisher, vs. self-publishing a book, as well as digging into some of startling numbers that have come out as a result.

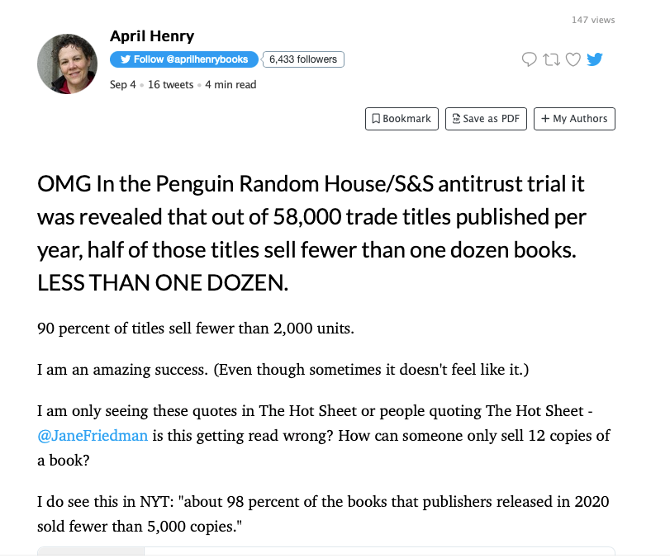

Let’s start with this:

This seems crazy, right?

But most books published traditionally sell painfully few copies, and one of the reasons I’ve been so fascinated with this trial is how it’s lifted the veil on a lot of what publishers do – or don’t do – to market books.

For example, it was revealed during this trial that Penguin Random House doesn’t start marketing most of their titles until they see that reader interest is beginning to increase.

This wait and see approach is a deadly way to market anything let alone books.

And we know that as books age, they become harder to market – getting influencers to review your book, getting media attention, etc. All that starts to decline the older a book gets.

The other surprising nugget was that publishers often see themselves as “angel investors” – which, by definition, is vastly different from any kind of expectations that authors would have for a publisher.

And the term angel investor is also passive, when you think of traditional angel investors, they invest their money and wait and see what happens, which is a sad way to acquire a book.

We know that a lot of authors (many of them genre fiction) are jumping ship and moving to indie publishing instead of staying with their publishing houses.

And it makes sense for them to do so, because lots of genre fiction sales come from eBooks, and it’s much more profitable for an author to grab those sales from Amazon (70% royalty from KDP) rather than share that with their publisher.

But what about the rest of us?

What about non-fiction authors, children’s books, commercial fiction, and the like?

There’s a big movement going on there as well, that makes considering self-publishing a book more lucrative.

And while unrelated to the Penguin Random House trial, there is another change looming on the horizon.

Namely that Barnes & Noble is shying away from carrying front list books and, instead, focusing on backlist books that have strong sales potential. Which seems counterintuitive to how they’ve always operated, meaning putting new release titles front and center for readers to browse and (hopefully) buy.

But more and more I’m finding that in every channel of traditional publishing and book selling, these places are less willing to take risks.

They’re in effect, becoming more like airport bookstores – only carrying the books they know are already selling.

This puts all authors, regardless of genre, in a precarious position.

Previously, if an author were to ask me why I’d suggest that they go the traditional publisher route, I would say that their distribution channels are unmatched – especially Penguin Random House. And by distribution, I mean the push into bookstores, airport stores, Walmart, Target, etc.

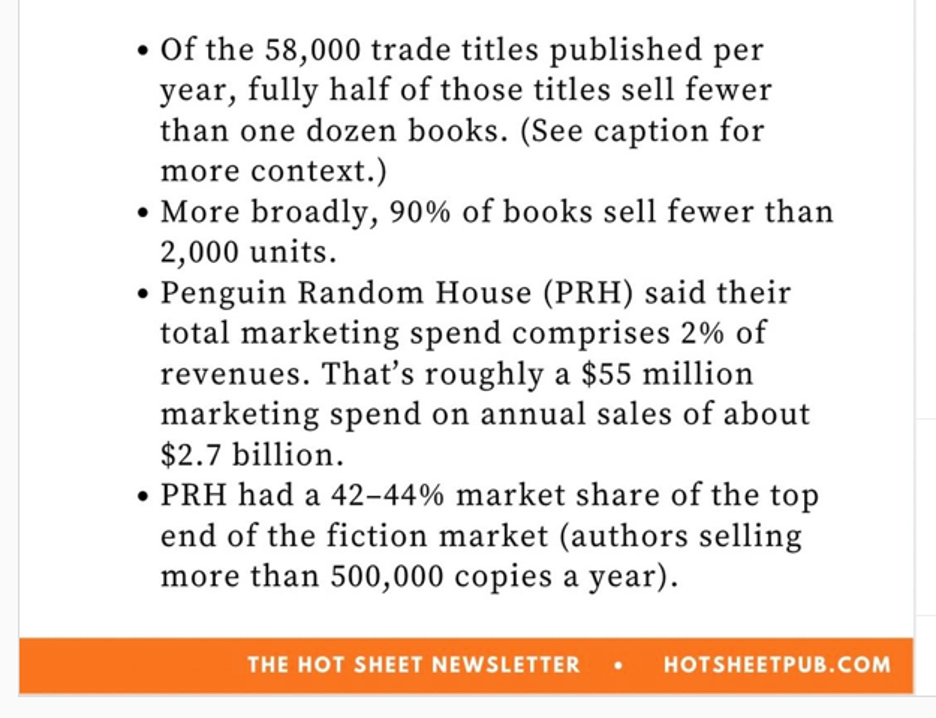

But then consider this, something else that came out of this trial was that publishers spend, on average, only 2% of their revenue on marketing.

You read that right, just 2%.

If you then factor in the Barnes & Noble piece I just mentioned, the distribution part of this becomes less impactful. Meaning that you’ll be lucky to get distribution of any kind, given how this model is currently set up.

Let me be clear: I don’t dislike traditional publishing, but they’re operating in an antiquated system that has worked for them previously, but really doesn’t support the author or, for that matter, further book sales.

Traditional publishing, as we know it, won’t be around much longer.

Why? Let’s say the DOJ decides that Penguin can buy (absorb) Simon & Schuster. This will shrink the market for authors.

With fewer options come fewer opportunities, and I can easily see them wanting to focus on books that are more of a sure thing (kind of like all the tabloid publishing they did during the Trump presidency).

And most authors aren’t sure things, unfortunately.

Let me be clear: this is not the death knell to publishing.

But I do think that it’s a model that just doesn’t work for most of us.

That said, self-publishing a book isn’t an “easy out” though I know it’s been treated as such by far too many authors.

The wakeup call that’s come out of this hearing: there are other options you should consider.

I raised the idea of self-publishing but there are also small presses who produce exceptional books and work hard for their authors.

And I foresee that boutique houses and small presses (different from hybrid publishers which are still, by and large, self-publishing) are going to rule this industry. Along with, of course, the well-done and smartly published indie titles.

It’s time to up your game, no more delays.

Not only because there are so many books vying for attention on Amazon, but because neither self-publishing a book or getting a publishing deal is the field of dreams.

Just because you wrote it (no matter how it’s published) doesn’t mean readers will beat a path to your door.

Being strategic is part of being an author, and I have a zillion blog posts and podcasts episodes dedicated to this (I’ll post a couple of recent episodes below if you want to delve into this more).

But suffice it to say, things are changing.

If you’re holding your book waiting for a big publisher to take your title, consider your options.

Consider a smaller house more dedicated to your success or be entirely independent and leave all your marketing and branding options open – it can sound scary but really, it’s the best option for your long-term success and branding.

No matter how you’re published, you still have to market.

So, knowing that, and how the industry is changing, what does your future look like?

If you’re self-publishing a book after being traditionally published in the past I’d like to hear what your deciding factors were.

Here’s one final image from @janefriedman with statistics from the trial:

And here is a very interesting panel discussion she did on this topic!

Resources and Free Downloads

What most authors don’t understand about self-publishing a book.

Why releasing a book is like starting a business.

How a publisher can kill your success.

Why self-publishing your book is extra lucrative if you’re planning a series.

Penny,

The panel discussion is really interesting and covers many of the issues that are as applicable at the smaller end of the market as at the top (read big) end of the market. I have spent hours on the phone and writing emails to publishers telling them that their marketing effort just doesn’t cut it. I do think that publishers are not connected to their readers, and your blog post says it all…the writing is on the wall and change is needed, otherwise the industry will lose out as disgruntled and disillusioned authors leave the industry.

Very helpful article and spot on. Question: do you have a list of small publishing houses? I’ve finished my southern fiction novel and am on the verge of self-publishing but hadn’t really thought of this small publishing house angle. Thanks. Arthur

Arthur hi there, I do not have a list handy unfortunately – sorry about that!

This is exactly what I try to educate my authors on when they come to me with their manuscript. So many want to be picked up by a big publishing house. I try to educate them on all the different avenues first so they know what is the best option for them. But so many just have this pie in the sky but traditional doesn’t mean they are going to be the next Harry Pottery. It is so hard to give them all the information in a black hole and unfortunately many publishers take advantage of hopeful authors with their first book. Why I have been in the process of making a documentary about the industry because it’s like the Wild Wild West with no rules or regulations. Anyone can throw up a shingle and try to publish books without any knowledge and take advantage of people.

Tara that’s exactly right – and good luck with the documentary, I can’t wait to see it!

Thank you Penny. Your posts and podcasts are valuable, genuine and generous, I am at awe. They’ve made me regained some hope after going through hundreds of mediocre rehashes of unstructured advice and scam marketing baits taking advantage of us, disoriented, eager new authors… you know what I’m talking about. And this post in particular has confirmed some misconceptions I had on traditional publishers, the numbers are indeed hair-rising! The traditional publishing model needs to evolve, as it did in the music industry, and as we authors are also faced with the only two possible choices: adapt or die. Thank you for enlightening us and kind regards from Spain!

Unbelievable. If these are accurate numbers, it is scary. I have a difficult time selecting good books to read.

Here are my numbers.

Selecting from Amazon randomly, the chances are 99.99 chances it is a book that I cannot go further than the first chapters. The percent goes to, say, 50% enjoying it if it is a “star review” from Kirkus, or 4-5 stars from a shop like IndieReader (there are other reputable review shops as well). And about the same (50%) if I buy one of the big five publishers.

Suppose Barnes & Noble (and Amazon) can filter out the bad books (I do not want to hurt anybody, but most of the books on Amazon and Barnes & Noble are rubbish).

In that case, self-publishing with them would be better than with a traditional publisher. But that is not possible. They do not have the means to review everybody’s book. Unless… they ask for a price and assign stars to the reviewed books. Until that happens, being accepted by a traditional publisher is the best validation.

But a total waste of years of time and effort marketing it to agents and publishers instead of working on another novel. (And it is time-consuming and effort-intensive to do it right) You then *if* a publisher takes it, they rarely properly edit it anymore, almost never market it, and you have a very limited ability to do so on your own. From an author’s point of view, I am afraid your points are simply wrong – for most authors anyway.

If some people choose not to look at my work because I self-publish, so be it. There is a very high chance I have made more money and certainly have been able to write and publish more work on my own.

Wow, that’s some statistics. Thanks for sharing

You’re very welcome! Glad you enjoyed the post!

For my last two books, roman a clef and regular novel, I have found small publishers with a short contract period. On expiration (or before if I can finagle it), I self-publish a second edition, new cover. The date for that new edition makes it appear as a new book. Having a traditional publisher affords the cachet needed to get it into libraries, and bookstores on consignment, and generally increases the trust in it. Then I can push the second edition, and don’t have to share the profits with a publisher.